You'll want to read Barro, chapter 8, before this lecture.

The business cycle is a tricky concept in economics. We pretend we can measure it, and make serious and deep efforts to understand it as a profession, but economists are largely powerless to do anything about business cycles. We experience them like anyone else. Even the wikipedia article defining it is continually in dispute.

What is a business cycle?

Well, we call it a 'cycle' because there seems to be an up and down relationship between real (or actual) GDP and trend (or potential) GDP. When an economy is below it's trend GDP, it might be heading into a recession. When an economy is above it's trend GDP in terms of it's real GDP, it might be experiencing a boom period.

GDP is assumed to break down into two parts, Real trend and cyclical. The cyclical part of GDP is the real part minus the trend part, and that is what we want to explain in this section of the course.

Barro shows us the proportionate deviation from trend GDP of the US Economy. What does it look like for Ireland?

It looks like the figure below.

We'd like to explain the existence and movement of business cycles through an equilibrium framework, so we'd like to consider changes in GDP, Y, C, etc, as they are affected following a shock, say, to technology,  , or to investment,

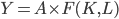

, or to investment,  . The starting place for an equilibrium business cycle model is the production function,

. The starting place for an equilibrium business cycle model is the production function,

.

.

In the short run, the capital stock  , is fixed. The assumption is that if

, is fixed. The assumption is that if  changes (say, computers fall out of the sky), that will effect

changes (say, computers fall out of the sky), that will effect  only.

only.

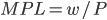

We derived the following two results in a previous lecture: the marginal product of labour will equal the real wage rate in equilibrium  . Similarly, the interest rate will equal the marginal product of capital, which will equal the return on capital minus the depreciation rate:

. Similarly, the interest rate will equal the marginal product of capital, which will equal the return on capital minus the depreciation rate:  .

.

Our equilibrium business cycle model will have to explain changes in consumption, saving, and investment, over the business cycle.

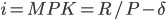

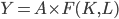

So, we need an expression for a household's budget constraint at any moment. Luckily, we have one:

.

.

This equation tells us the household's consumption  and saving

and saving  decision is dependent on it's real wage rate

decision is dependent on it's real wage rate  and it's real asset income,

and it's real asset income,  .

.

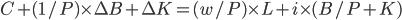

If we aggregate all the household's budget constraints in the economy, we have

,

,

which says that consumption and net investment is equal to real GDP minus depreciation, or real net domestic product.

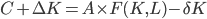

If we substitute in the production function  , we get

, we get

What will the income effect be on  from a change in

from a change in  ? Because depreciation is fixed in the short run, we have technology increasing real income, and consumption will rise. The intertemporal substitution effect fights against the income effect on this, so no sharp prediction can be made.

? Because depreciation is fixed in the short run, we have technology increasing real income, and consumption will rise. The intertemporal substitution effect fights against the income effect on this, so no sharp prediction can be made.

Consumption and Investment

What does consumption and investment look like over the business cycle in Ireland?

Proportional values (using Logarithms) look like this:

We'll go through more examples in the lectures.

Finally, here are the slides:

Download them here:

What my college-level courses in economics failed to explain or even consider was the unique role of land markets as a driver of the so-called business cycle. Not until I chanced on the works of Henry George did the boom-to-bust nature of markets really make sense. George did not use these terms, but his important insight is that price does not (as neo-classical economic theory prescribes) clear the market for nature (i.e., for "land" as a first factor of production). As prices for locations are rising, the supply curve for locations defies economic theory and leans to the left because of hoarding and speculation. This is what has occurred globally over the last 15 or 16 years to an extent never before experienced. Firms seeking to preserve profit margins by moving to locations where the cost of production is lower are finding few such locations where land prices have not already skyrocketed. These aggregate stresses have converged, and we are being pulled into a deep and prolonged global recession -- and, unless our governments pursue wise changes in policy, conditions that will mirror those of the Great Depression.

Hi Edward,

Henry George has a great place in my heart since reading The Worldly Philosophers. Heilbroner is pretty dismissive of George's analysis of the impact of land pricing on the economy, but that's as far as my reading takes me. Can you recommend any expository papers or books I could share with my students?

Best,

Stephen

Stephen, you asked awhile back whether I could recommend readings that resurrect Henry George's treatment of political economy. Quite frankly, a Google search on "Henry George" will bring up a long list of links and readings. A decade ago, I created an online education and research project called the School of Cooperative Individualism to bring together in one place key writings by many authors who shared Henry George's perspectives (but also writings on political economy, generally). The online library at the SCI website is huge and continues to expand. Several economics professors have graciously permitted me to include their papers. Others whose writings are in the public domain are representated as well. From the latter group I would recommend Harry Gunnison Brown and Arthur Becker. From economists who continue to teach and write are Mason Gaffney, Nic Tideman, Fred Foldvary and Kris Fader. Also, Nobel Prize winner William Vickrey was something of an admirer of Henry George's work.

Feel free to point your students in the direction of the SCI project.

And, finally, Henry George's seminal work, Progress and Poverty, has recently been modernized and printed in softcover by the Robert Schalkenbach Foundation in New York. The result is quite good, I think.