[print_link]

This lecture is about money. Money takes several forms in the modern economy, and has several functions. In particular, money as we'll talk about it in lectures is really an aggregate of cash, deposits in banks, credit available, and

Briefly, the functions of money are:

Medium of Exchange. acts as a medium of exchange – hence permits a time interval between buying & selling commodities; thus eliminates need for a ‘double coincidence of wants’ implied by bartering, as one can sell Goods & Services without simultaneously purchasing.

Store of Value. Money is able to perform function as Medium of Exchange because it retains value over time.

Standard of Deferred Payment. Loans & future payments are agreed and contracted in money terms, as money units are accepted as the means of settling future accounts.

Unit of Account. The unit of account in which prices quoted and accounting records kept.

Standards of counted money:

The M1 standard is used in looking at the total currency in circulation as well as the deposits held in banks. The figures below show first the level of M1 in the Euro area, and second, the currency in circulation in the Euro area from 1998 to 2008 (find it's source data here):

Fig 1. Monetary Aggregate M1. Source: ECB Statistical Warehouse

Fig 2. Currency in circulation in the Euro area. Source: ECB statistical warehouse

Barro page 235 shows us ratios of currency to nominal GDP. For Ireland, by year, these are

1960: 0.117

1980: 0.077

2000: 0.052

The takeaway message is: the ratio of currency to GDP declined over time in most countries.

Demand for Money

In the same fashion as the previous lecture, I'll change the demand and supply of money to account for the differences we see in the real-world.

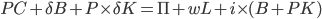

In what follows, we'll assume money is only held for transactions, and so the interest rate on money is zero, because other assets like Bonds are better stores of value, when we look to the future. The household's demand for money is dependent on its nominal budget constraint:

Which simply says nominal consumption and nominal saving must equal nominal income.

Households can, if they choose, reduce the amount of cash money they have on hand by performing more transactions. This costs them something though, and these costs are summarised as transactions costs. Because these transactions are costly, the household trades off holding less cash by holding more of its income in assets Thus by reducing their levels of  , the households raise their levels of

, the households raise their levels of  The higher the interest rate,

The higher the interest rate,  , the greater the incentive to increase holdings of bonds and other capital assets.

, the greater the incentive to increase holdings of bonds and other capital assets.

The price level  only affects the nominal values of goods and services in the economy---the real demand for money,

only affects the nominal values of goods and services in the economy---the real demand for money,  does not change when

does not change when  changes, because if the price level rises and affects all the components of the household's budget constraint equally, their purchasing power remains unchanged.

changes, because if the price level rises and affects all the components of the household's budget constraint equally, their purchasing power remains unchanged.

The nominal money demand function can be specified as the price level times a function of the level of economic activity and the interest rate:

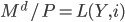

And in real terms, this becomes

Supply of Money

When the nominal quantity of money supplied equals the nominal quantity of money demanded, we have that  . Substituting

. Substituting  into the equation above, we have

into the equation above, we have

What happens when the nominal quantity of money changes?

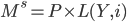

Recall what we saw last lecture: with the macro model changed to reflect unemployed capital resources and labour resources, the interest rate became modified to

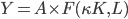

And, output is now given by

As we can see in the figure below, if we increase the nominal quantity of money in the system, output,  , doesn't change. We'll show you why in lectures. So increasing the money supply won't help us get output higher. This is the neutrality of money argument.

, doesn't change. We'll show you why in lectures. So increasing the money supply won't help us get output higher. This is the neutrality of money argument.

Figure 3. Increases in the supply of money don't do much for you. Source: Barro, page 244.

If demand for money changes, what happens to the supply of money?

As we'll show in lectures, a decrease in the demand for money looks fairly similar to the case shown above for an increase in the money supply, except here the change is not fully neutral.

Slides for tomorrow's lecture are below.