Time is short this week, so a truncated two lectures in one for you, based on the end of chapter 8 and all of chapter 9 of ze textbooky-wook.

Click below for the notes, kids.

[print_link]

1. Costs, Redux.

Last week we looked at the theory of costs. We defined total cost, marginal cost, and average cost.

We saw that total cost was the sum of fixed costs and variables,

, average cost was the division of total cost by the quantity of output produced,

, average cost was the division of total cost by the quantity of output produced,  and Marginal cost is the change in cost for a one unit change in output,

and Marginal cost is the change in cost for a one unit change in output,  . We saw their relationship using a Mathematica demonstration.

. We saw their relationship using a Mathematica demonstration.

We saw the difference between short run costs and long costs. The short run has the disadvantage of fixed costs, which are costs associated with inputs one can't change in the short run. The long run allows one to be more flexible with respect to costs. When we look at per-unit short run cost curves, we see the familiar relationship, as in the picture below. Play with these curves using the Mathematica demonstration.

1.1 What shifts cost curves in the short run?

We'll go through these in lecture:

- Changes in input prices.

- Technological Innovation

- Economies of Scope

The relationship between long run and short run cost curves can be seen using this Mathematica demonstration, and yes folks, we'll go there.

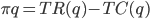

2. Profit Maximisation and Supply

Firms exist to capture economies of scale by reducing transactions costs. This is the Coase Theorem. The firm is assumed to want the most for itself and its shareholders or owners. The firm is assumed in simple models to try to maximize its profits,  , which we defined in the last lecture as

, which we defined in the last lecture as

,

,where  represents the total revenues the firm gets for producing some level of output

represents the total revenues the firm gets for producing some level of output  , and

, and  represents the total cost the firm incurs for producing some level of output,

represents the total cost the firm incurs for producing some level of output,  .

.

The firm has to choose what level of output  to produce. Remembering the definition of marginal cost:

to produce. Remembering the definition of marginal cost:  , we'll show in lectures that the profits of the firm reach a maximum when the slope of the total cost curve is equal to the slope of the total revenue curve, or, at the optimum level of output,

, we'll show in lectures that the profits of the firm reach a maximum when the slope of the total cost curve is equal to the slope of the total revenue curve, or, at the optimum level of output,  ,

,

Or:

(It's really important to remember that one, so I'm putting it in red.)

How does the firm actually do this? By trial and error. The firm will experience  for output levels below

for output levels below  , which tell it to produce more output,

, which tell it to produce more output,  , until it equals or exceeds

, until it equals or exceeds  . If the firm produces more output than

. If the firm produces more output than  , it will experience

, it will experience  , so it is losing money on each additional sale. There are a fair few examples of this situation occurring in real life, notably in the music industry.

, so it is losing money on each additional sale. There are a fair few examples of this situation occurring in real life, notably in the music industry.

For example, a popular story about the New Order song, "Blue Monday" holds that the single's die-cut sleeve, created by Factory designer Peter Saville, cost so much to produce that Factory Records actually lost money on each copy sold.  . D'oh.

. D'oh.

How does the firm decide what inputs to produce? The marginal conditions give us simple rules for this decision. Mathematically the firm wants the biggest difference between its Revenues,  , and its costs

, and its costs  . The

. The

One important idea we'll have a look at in the lecture is the concept of the firm as Price Taker.

A price taker is a firm or individual whose decisions regarding buying or selling have no effect on the prevailing market price of a good or service. For a price taking firm it must hold that

If the firm experiences a downward-sloping demand curve, then we can say with confidence that  , because when you're selling one more unit, and that sale causes the price to decline, then you can be sure the firm's

, because when you're selling one more unit, and that sale causes the price to decline, then you can be sure the firm's  will be less than

will be less than  . We'll show a Mathematica demonstration of this property in class, if the program actually works for me this time 🙂

. We'll show a Mathematica demonstration of this property in class, if the program actually works for me this time 🙂

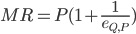

We'll also see how the marginal revenue of the price taking firm is dependent on the price elasticity of demand for that product. Recall that elasticity,  , defined at a certain price

, defined at a certain price  and quantity

and quantity  , is defined as the percentage change in quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in price.

, is defined as the percentage change in quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in price.

(elasticity of demand)

When the price change occurs across an area of the demand curve which is elastic, so  , the marginal revenue will be greater than 0. When

, the marginal revenue will be greater than 0. When  , so demand is inelastic, marginal revenue will be negative. The relationship can be summarised as

, so demand is inelastic, marginal revenue will be negative. The relationship can be summarised as

We'll also look at the supply decision of the firm. The firm, if it is a price taker, will find itself in the short run trying to maximise profits by picking  to get revenues above short run variable cost. The firm, as we'll see, will shut down when

to get revenues above short run variable cost. The firm, as we'll see, will shut down when  , and continue to operate anywhere above that price.

, and continue to operate anywhere above that price.

Related articles

- EC4004, Ecs for Business, Lecture 4: Market Demand and Elasticity

- Claims about food prices

- Does my brain look fat?

- Public Transit Up, Driving Down as Gas Prices Increase

- Virtual Worlds for Fun and Research [Academia]