Budgets are all about context. They can’t be understood without a sense of the political situation the government of the day finds itself in, or without a good sense of the state of the international economy. Be assured the government has a good sense of both, if not a sure sense of how to deal with either.

Ministers are far from the disconnected, remote beings bombing around in the back of Mercs they are often caricatured as. It’s closer to the truth to say being a minister makes you hyper-connected. They hear many, many things. Everyone wants a word with them. Everyone has a request or three. Officials fill their heads with analysis of all kinds, and of course, they all read the papers to find out what people are saying about them.

The political situation means the government must solve a constrained optimisation problem, where the constraints are the availability of funds from taxation, the fiscal rules, the needs of three coalition parties, and the expectations of the public. The optimum those crafting the budget needed to reach is the stability required to rule, rather than the maximum welfare of citizens.

(A digression: if you think there aren’t three parties in coalition, just look at how Fianna Fáil both sponsored, and rushed to take credit for, the pension increases we saw in Tuesday’s budget. It’s a very Irish three-party coalition, so much so that RTÉ, not well-known for early acknowledgments of reality, wanted Michael Noonan to debate the finance spokesman of the main opposition party—Pearse Doherty—on the night of the budget).

The domestic politics constrained any major policy initiative such as trying to sort the water issue, itself kicked into the long grass and not mentioned once on Budget Day, or dealing with our demographic challenges.

In 2021, there will be over 108,000 more people over 65, and each of them will require health and social protection expenditure, paid for using the taxes of 108,000 fewer workers. Nothing in this budget changed that.

Flooding is a serious issue in this country, and yet the OPW’s increase for funding was modest. Everyone bangs the drum about the long-term investment in our society education represents, but of the €1.58 billion we spend on higher education in 2016, the government increased it by just €0.036 billion.

These are just three examples, there are many more. Show me your budget and I’ll show you what you value, to paraphrase Joe Biden. This budget showed the government valued stability and optimised for that. It did the best it could, given the circumstances. That’s the nature of constrained optimisation.

This budget had caution written all over it. As the Roman historian Tacitus wrote more than 2000 years ago, “The desire for safety stands against every great and noble enterprise.”

Enough with the quotes. The post-budget discourse has been, quite frankly, pathetic. It involved only one question: how much did I, or people like me, get?

We saw collective eye-rolling from all and sundry for the ‘paltry’ fiver increase they got, as everyone conveniently forgot that this time five years ago, we were looking at swingeing tax increases and spending decreases. Anybody over 23 should remember that in 2009, we had not one, but two austerity budgets.

But no, the public expectation is that everything should be restored to boom levels now, if not sooner, without a recognition that what brought us these boom conditions was an unsustainable bubble which damaged our economy and society as it grew, to say nothing of when it burst.

The real question we should ask is: where does this budget take us? What is the key instrument of government policy being used to achieve in the medium term?

The quality of analysis has jumped up a step in recent years. This budget was a treat for policy wonks like myself with a raft of extra information and research on the sectoral impacts of Brexit – bad for indigenous Irish firms – as well as a comprehensive overview of the childcare sector and our policy response to having some of the most expensive childcare in the world. However, it is still not clear what we’re trying to achieve.

Take health and housing, two of the big crisis areas in the country at the moment. It’s probably a good idea to take health and children and youth affairs together as they were once the same department.

Austerity ended in 2013. Since 2013, these department received increases in their budgets, bringing them from around €13 billion to around €16 billion, including pay, non pay, pensions, and capital spending. The most ever spent by the state.

One billion euro extra was allocated for health alone this year, focused on just over 100,000 people running a relatively expensive health service with relatively poor outcomes compared to countries we’d like to be like. Minister Simon Harris has a lot to play with, but much of this extra spending isn’t going to effect structural changes towards the primary-care sector, it is going to try and solve emergency medical issues.

Minister Katherine Zappone is the big winner from this budget, with the after-school plans announced by her predecessor, James Reilly, being brought to fruition on her watch.

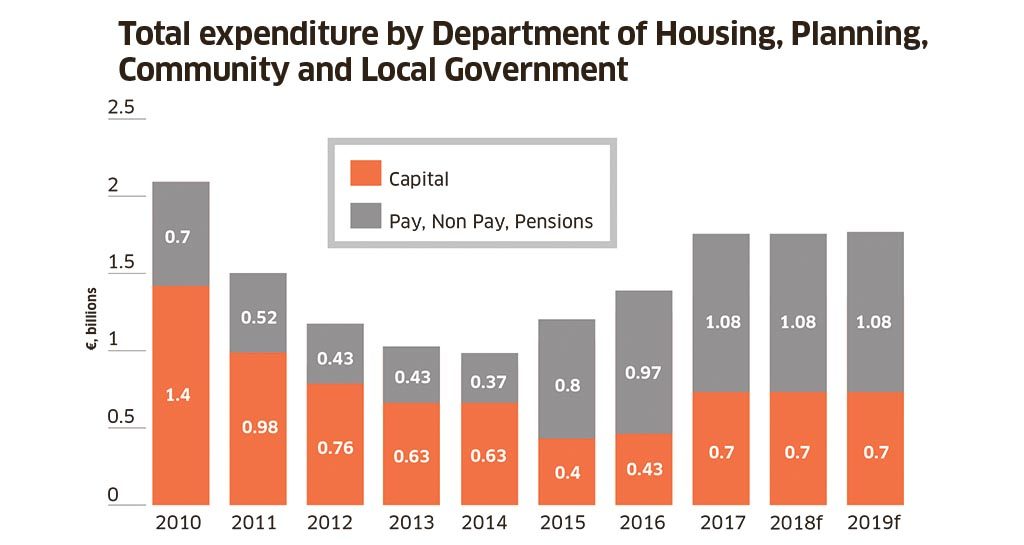

This has the potential to end Ireland’s long-running problem with low work intensity households and will be beneficial for those on lower incomes. When it comes to housing, Simon Coveney has a very tough job, in that unlike the Department of Health, his department was starved of funds for several years as the housing crisis took hold. These facts are not entirely unrelated.

In 2010, Minister Coveney’s department had over €2 billion to spend. This was cut to €1 billion by 2015, and is now being increased by over €700 million of capital expenditure every year from 2017 to 2019. However, it is still well below the boom levels we’ve seen, and will probably require more capital spending as funds become available. The state is due to spend half of what it spent in 2010 on capital in 2017, 2018 and 2019 to address the housing crisis.

Look at where this money comes from. Income taxes, in the form of USC reductions are being reduced, though this is probably offset a little with unindexed tax bands. With 150,000 fewer people at work compared to 2008, fewer workers are supporting more people, and this trend is due to continue.

With highly volatile corporation taxes doing much of the ‘extra’ lifting to fund increases in health, housing, and social protection, the state’s revenue base is being reduced, and there is a real chance external factors could effect this, because much of our corporation taxes come from a tiny number of multinationals. If their fortunes change, so do ours.

The tax credit for housing was pure stupidity, an expensive work around of the Central Bank’s mortgage rules that has infected the housing market with positive expectation. Since the Budget Day announcement, many homes on daft.ie and other websites have seen price increases. Economists don’t know much, but they do understand supply and demand. They invented it. I’ve yet to find an economist in favour of this policy.

The Brexit challenge isn’t being directly addressed in Budget 2017, but I don’t think we should chastise the government for this. Brexit hasn’t happened, and the government was wise to simply throw a few shapes at it while doing more research and trying to influence the eventual outcome quietly.

An overreaction would have been very costly, and would have come at the expense of health, housing, or social protection spending, potentially for nothing.

The government must Brexit-proof its forecasts, however. All of the forecasts are based on the euro trading at 0.85 to sterling. Today that number is 0.92. That might not sound like a lot, but it weakens our exports, and so lowers our growth. A better technique for forecasting based on currency ranges has to be developed,

We have to see this timid budget in its context. Across the developed world, it is the case that minority governments produce centrist and non-controversial outcomes, and nowhere is this more apparent than in fiscal policy. You can’t solve the constrained optimisation problem otherwise.

We should be patient. This is the first political experiment of its kind after 70 years of the Fine Gael Fianna Fáil duopoly, where they are effectively governing together in coalition with independents.

Our new budgeting structures will strip the possibility of stupid fiscal wheezes like decentralisation out of the system, but at the cost of gradualist capital planning. The public can decide whether this new form of government solves their problems better than the previous form, though looking at the coverage of Budget 2017, they’ll decide by asking what’s in it for them.