Like many people, I wake up every morning and ask myself: what has Donald Trump done overnight? It’s hard to keep up with everything he’s done.

Everyone is asking: what does Trump mean for me, my family and my business? Should I buy a house if I work for a multinational? Should I travel to the US if I’ve read an anti-Trump tweet? Should I invest if he pulls up tariffs and increases the price my customers will pay for my goods? Should I buy bonds or equities for my retirement? What will the economic consequences of Trump be?

In life it is best to plan for the worst and hope for the best. Here is the worst. It’s going to get a bit grim for a few paragraphs, but stay with me. I’ll take you to Mordor and back to the Shire again. I promise.

The Holocaust Museum is one of the world’s great museums and a testament to the horror unbridled nationalism can unleash. Last week it released two statements. The first was a condemnation of some of what Trump has done to refugees and immigrants. The second was a picture of a poster by political scientist Laurence Britt, warning against the early warning signs of fascism.

Those signs are a powerful and continuing nationalism, disdain for human rights, identification of enemies as a unifying cause, supremacy of the military, rampant sexism, controlled mass media, obsession with national security, religion and government intertwined, corporate power protected, labour power suppressed, disdain for intellectuals and the arts, obsession with crime and punishment, rampant cronyism and corruption, and fraudulent elections.

Did you find yourself ‘ticking off’ each element in the list? I did.

Trump’s two-week-old presidency has seen him push his America First agenda, ban immigrants from seven Muslim-majority countries (but give Christians in those countries free passage), force the Department of Homeland Security to publish weekly lists of crimes committed by immigrants, block federal funding from family planning organisations, some of whom offer abortions, halt the entire refugee process into the US, withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, cut funding from federal arts programmes, freeze hiring by the federal government, call for 10,000 more immigration officers, antagonise China, North Korea and Iran, and relax sanctions on Russia.

One of Trump’s economic advisers, who I’m not going to dignify by calling him an economist, called Germany a currency manipulator. Trump’s ambassador to Europe wants to tear the European Union down and has compared it to the Soviet Union.

The United States of America has been the pillar of the post-war world. Its navy secures the sea for trade and dampens any chance of outright war. Its armies surround the globe. Its wealth and soft power allow it to disrupt potential threats to its security in other countries. Other countries that don’t trust each other can work through the US to get things done. After a bruising series of encounters with the premiers of Mexico and Australia, much of the trust the US has spent decades building is eroding in weeks. Every summit of world leaders will now have as its unwritten agenda item: how do we deal with Trump?

‘Flawed democracy’

Five hours after assuming the presidency, Trump registered to contest the 2020 presidential election. He can raise funds through political action committees to fund attack ads, and cannot be reported about in the same way as if he wasn’t a political candidate.

The Economist Intelligence Unit has downgraded the US to a “flawed democracy”. This downgrade reflects Americans’ drop in confidence in governmental institutions. In 1958, 80 per cent of Americans surveyed trusted their government. In 2017, less than 20 per cent do.

Next week, Trump plans to pull apart a series of financial laws and regulations designed to force the people who sell financial products like pensions to act in the customers’ interests, and not their own, as well as regulations forcing banks to hold more capital to offset any future banking crisis. Trump’s not draining the swamp. He’s filling it up, and stoking another banking crisis. Ireland will suffer.

Trump’s communications team has replaced briefing the press with lying to them, removing them and, in the case of one US citizen with an accent, demanding they get out of his country. And it is his country.

Four more years of this, folks.

The US is going to be a dark place for a long time, but it’s still a fantastic country

Trump took a few swipes at repealing the Affordable Care Act, but with nothing concrete to replace it, this is all smoke and mirrors. President Trump is engaged in the production, manufacture, and distribution of high-quality bullshit, but it should be noted, in fairness, that every president wanted to be seen to hit the ground running and produced some bullshit while doing so. Barack Obama, for example, ordered Guantanamo Bay closed eight years ago, in one of his first acts in office. The world’s most infamous prison is still there today, a stain on the US and on the world.

Another word on Obama. He’s looking pretty good now compared with Trump, but we should remember that he deported nearly three million people from the US, used drones to kill civilians, and placed a temporary refugee ban on Iraq. His administration’s approach to refugees was only moderately better than Trump’s. That’s not whataboutery, it’s just a way of saying that the Obama administration was very far from perfect. Trump’s administration is much, much worse, staffed as it is with white supremacists.

Read the Holocaust Museum’s list again. It seems clear that Ireland should plan for the US becoming a place where fascists rule the executive branch of government, and hope the civil institutions of the state are strong enough to resist for eight years.

So much for Mordor. Back to the Shire. What does all this mean for the man trying to buy the house in Dublin or the woman saving for her retirement?

Fascism means a relentless focus on the nation. The US is the major foreign direct investor in Ireland. Ireland is very vulnerable to the re-nationalisation of US funds.

Open economies

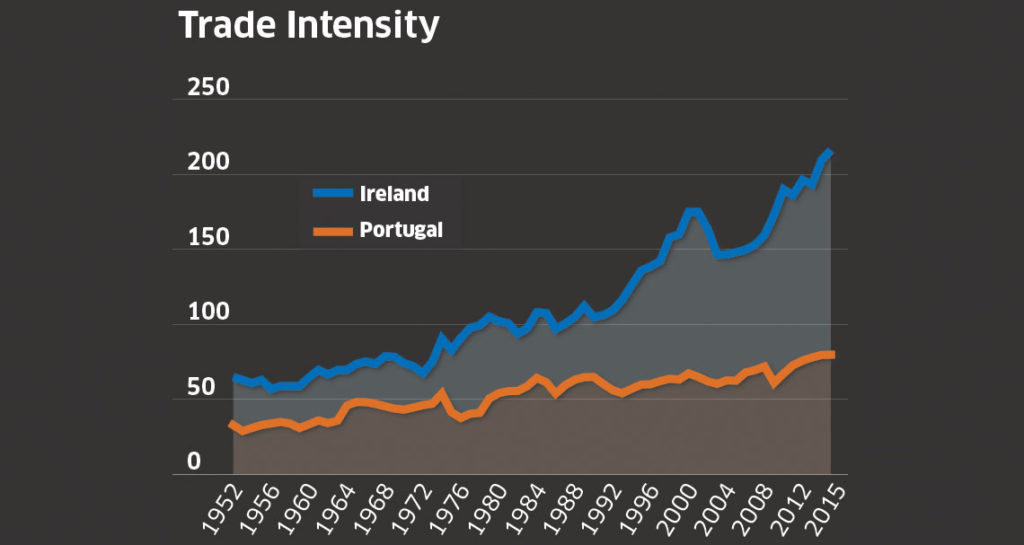

Look at the chart above. It is a measure of openness called the trade intensity ratio. You add the value of a country’s exports and imports together, and divide it by the value of the country’s output, gross domestic product. You’re looking at Ireland from 1952 to 2015 and, for comparison, another small open economy, Portugal.

The degree of openness of an economy matters for many reasons. The most important reason is exposure to macroeconomic risk. Risk can have both an upside and a downside. When the global economy is expanding, and the degree of interconnection between markets — sometimes called globalisation — is increasing, countries that are very open to trade see large rises in their living standards. When the global economy moves into a contraction phase, and Trump, Brexit, Marine Le Pen and other nationalists promise this, open economies tend to suffer more, as they are more exposed to the downturn than other economies with larger domestic sectors.

Portugal doubled its level of openness over the 65-year period shown in the chart, from 33 in 1952 to 80 in 2015. Portugal’s performance can partially be explained as a result of the “Estado Novo” regime which ruled in the 1960s and 1970s and urged increased economic integration and trade with Europe.

This openness to trade and integration was retarded somewhat after the Carnation Revolution of 1974, a military coup which ushered in nationalisation of industries (more than 200 in two years) and a period of economic stagnation. In the 1980s, Portugal opened up to trade once more and, significantly, joined the European Union in 1986, but has never had a large internationally traded sector.

Ireland is an outlier. In 1952, our level of openness was almost as high as Portugal’s was in 2010. As a result of a combination of history, geography, its industrial structure, and the over-arching policy of export-led growth since the late 1950s, Ireland’s level of openness dwarfs that of many other economies. Other countries and protectorates whose trade intensity ratios exceed 100 per cent include the Hong Kong Special Administrative Zone, Luxembourg, Singapore, Malta, Vietnam, the Slovak Republic, and the United Arab Emirates. Any re-nationalisation by a fascist US administration would harm highly open economies like these disproportionately.

Smaller states like Ireland must be very careful to curb the inflow of foreign capital into their domestic economies. The argument, which dates back (at least) to Walter Bagehot in 1873, goes that increased international capital inflows – especially in the form of debt – amplify financial risks to the domestic banking sector.

This is because the greater availability of investible capital to domestic banks increases the funds intermediated by the financial sector, fuelling excessive growth in lending, and magnifying the impact of a banking crisis. Come on. You’re reading The Sunday Business Post. You know all of this. The banking regulations Trump plans to remove increase the chances of a domestic banking crisis here.

Should my friend buy his house? Yes, but borrow the smallest amount you can, and pay down the debt as quickly as humanly possible. Trump’s moves to restrict US capital going abroad mean FDI flows from the US may dwindle, harming my friend’s job prospects as well as the domestic housing market. As I argued last week, shifting away from a focus on multinationals should now be a key focus of the Irish government.

Should I invest if Trump pulls up tariffs and increases the price my customers will pay for my goods? Tariffs are taxes that fall randomly on different people. Trump has signalled tariffs for Mexico and, in particular, for manufactured goods. To the extent that Ireland trades mainly in ICT and financial services, you should be okay.

What about my friend saving for her retirement — bonds or equities? It’s got to be equities all the way. Remember, the Holocaust Museum promises us, corporate power will be protected at all costs.

This means profits will soar, and companies that issue equity will remit some of that back to equity holders. Warren Buffett recently bought $12 billion-worth of equities, for example.

Should you travel to the US if you’ve read an anti-Trump tweet? Yes, but be careful. The US is going to be a dark place for a long time but it is still a fantastic country with amazing people and resources. If you can support civil society fighting Trump, do so.

We need to plan for the worst and hope for the best. To paraphrase the great historian Joe Lee, small states have to be strategic to survive. The strategy Ireland needs to pursue is the softest Brexit possible and ever-tighter integration with Europe, which is emerging as the only western bulwark against Trump. Angela Merkel is, for now, the leader of the free world, and we need to support her.