Housing is the fundamental public policy problem. Everyone needs a roof over their head, preferably for a long time so they can become part of a community, surrounded by high quality services they can access if they like. This is the dream of urban planners, economists and the political system, not to mention just about every taxpayer and citizen. The reality is far different.

Housing is something you consume and something you invest in. The social use of housing is typically what we talk about when we use words like ‘home’. When we use words such as ‘property’, we are often talking about investment. When we use words like ‘stunning cosy property close to transport links’, we are most likely trying to sell a wheelie bin between train tracks.

The most obvious thing you can say about housing in Ireland in 2017 is ‘we need more of it, and if we increase supply, prices will go down’. This statement naively assumes there is a textbook account of supply and demand going on in the housing market. It assumes houses are like oranges or mobile phones. When you increase the supply of these things, the price should drop. The data, and international evidence, suggests the opposite when it comes to housing.

Private sector builders don’t build houses to watch the prices drop. They start from the site the house is going to be built on. They work out how much to pay for that site by figuring out first how much they think the house will sell for, factoring in building costs and their profit margin and the likely inflation of prices. So the supply of privately-built houses never really exerts downward pressure on the price of houses when the private sector does all the building, and the government simply allows household credit to expand to make the homes affordable. The result is a deeply indebted society that is made more fragile to shocks to its income.

Trinity College Dublin’s Ronan Lyons recently reported an annual increase of 9 per cent in house prices nationally and a 10.2 per cent increase in Dublin, where the average house price is €347,000.

Research last week from the Central Bank shows us just how fragile Irish households are. Apostolos Fasianos, my PhD student at the University of Limerick, and his colleagues Drs Reamonn Lydon and Tara McIndoe-Calder, show that, compared with other countries, Irish borrowers born from the mid-1960s through to the early 1980s have substantially higher levels of debt. They find debt in Ireland is more concentrated in property, and the low-interest environment since 2008 has been beneficial to these highly-indebted households. Fasianos’ research also means that any changes to interest rates will have a negative effect on these households.

The private sector building more houses is unlikely to cause house prices to fall. If we want house prices to fall — and that is a very big if, which I’ll come to in a minute – the solution is to do what we did in the 1930s and 1940s and have the state contract directly to build housing on sites the state owns, and then rent the homes back to people.

There are other models where the state gets a partial share and the tenant a partial share, but these are details. What matters is that the social use of housing — as opposed to the market or investment use of housing — takes precedence.

Public housing

Right now there is a very large, and unquantifiable, transfer taking place from those who want to buy to those who have something to sell, mediated by the banking system. The best way to think about this transfer, and the incentives it supplies, is by examining individual balance sheets. A balance sheet is a statement of the value at a point in time of what you own, called your assets, and what you owe, called your liabilities. The difference between the value of your assets and the value of your liabilities is called your equity. As everyone reading this paper knows, you can have positive and negative equity.

Imagine you are a developer or, more likely these days, a vulture fund, sitting on some land, say four acres near Dublin. The value of your site is rising every day as you look out the window and read the paper suggesting demand for housing is increasing.

The Central Bank’s recent relaxation of its rules around loans and the government’s assistance in helping increase the amount buyers could afford, has helped make homes more affordable for those people just about to buy, and also pushed the price up for those buying in the future. As a land-holding developer, it is in your interests to wait until you can command the price you need to satisfy both the residual site value and the profit margin you can make.

Coveney says we’re building again after the crisis. But there is mounting evidence that the figures supplied by his department don’t add up

The value of your assets is also rising, so even if you do nothing, you can pay yourself more this year anyway. So your balance sheet is not telling you to build more houses to lower prices. Far from it. There is a natural feedback mechanism as well — as house prices rise, so too does the value of the land, and because the land value is rising, so must the price of the house. This ‘accelerator’ process is at the heart of many economic crises. It also makes some people very, very rich.

Look at the balance sheets of would-be homeowners. You see that every time a property they want goes up in price, they get poorer, either because they don’t end up buying the asset they want, or because they do get to buy the asset, but at an inflated price they have to borrow more to afford. They become more fragile.

Their interests are not served in either extending the amount of credit available or in incentivising the private sector to build more houses, because neither acts to pull house prices down.

Only public housing does that. But a large expansion of public housing harms the balance sheets of those with land and those who already own homes, and so is against the interests of this powerful majority of households and landowning development firms.

The far less powerful, and typically younger would-be homeowners are left to suffer either now, by crowding a poorly regulated and poorly inspected rental market, or by buying a house they can barely afford, which will make them poorer in the future, also.

Spreading fake news

Minister for Housing Simon Coveney says Ireland is building again after the crisis. But there’s mounting evidence that the figures his department are supplying don’t add up. Imagine you’re looking at a bathtub with some water in it. The stock of water is the level of water in the tub. The flow of water is what comes in from the tap. When it comes to housing, we care about both the stock and the flow.

Let’s take the stock of housing first. Census data released last week show 33,436 of the people who responded to the census were living in homes completed between 2011 and April 2016. Figures from the Department of Housing suggest the stock of homes built during this period is 55,250.

Someone is wrong, and badly wrong. DIT’s Dr Lorcan Sirr has made this point repeatedly in his columns in the Sunday Times. In the Engineers Journal, architect Mel Reynolds has also been looking into the numbers being reported by the housing department. Their work and my own digging convince me something is not right.

To be fair, this may just be a counting issue. The Department of Housing counts completions based on new ESB meter connections. When a property has been vacant for two years or more — and loads of Irish properties built and abandoned during the bust have this feature – new connection numbers are issued, so we might just have double-counting problems, which would at least partially explain the divergence between the census figures and the Department’s.

Even within the Department’s figures, there is a divergence between the number of commencement notices which are received by planning authorities, and the number of completions, though the commencement notices represent the planned start of a build, and the connections are supposed to measure the end of the build. Again, the fact that there was a gigantic housing crisis in the middle of the period we’re looking at probably explains a lot of the divergence in the estimates of the stock.

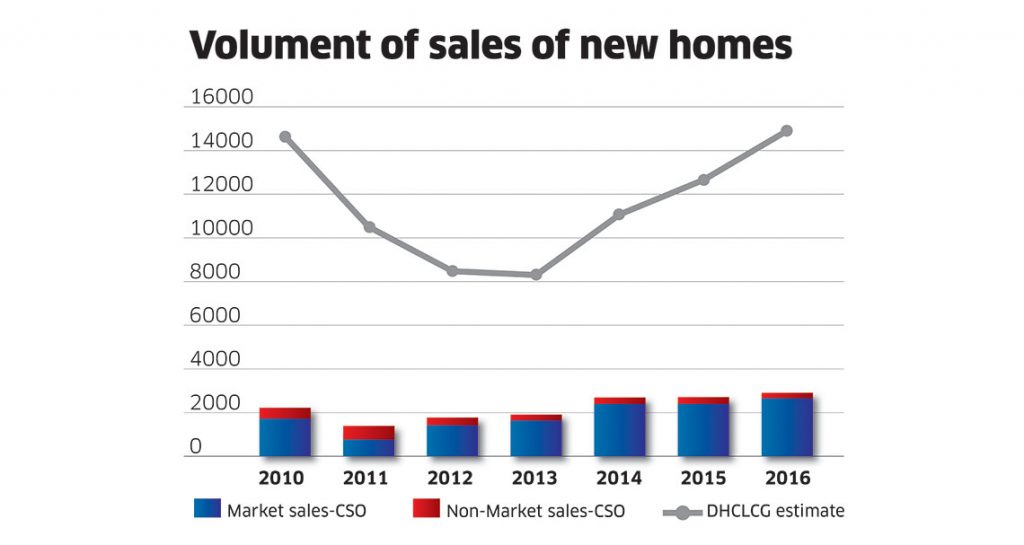

The flow of new housing as reported by the Department of Housing also seems very high relative to the amount of tax paid on these properties. The 2016 figure of 14,932 completions seems at odds with the stamp duty amount paid to the state for new homes. In 2016 the state took in around €1.192 billion in stamp duty, and this is levied at 1 per cent of the sale price. But this includes commercial property as well, so is not a good indicator.

The CSO gives us a breakdown of the value and volume of new homes sold. In 2016, 2,883 new homes were sold, corresponding to the new supply, and this was recorded as worth €751 million. But the Department of Housing is saying we built over 14,000 new homes. Other market-based indicators available in the public domain like the volume of new home loans, one-off building commencements and what we might call estate home type transactions suggest we’re building fewer new homes.

The stocks don’t cohere. The flows don’t either. Something is either wrong with the bathtub, or the way we are measuring the problem.

The department needs to begin counting housing using the Building Control Management System, which it already has, and has had electronically since 2014, but for some reason does not report publicly. This is the gold standard in counting of new homes. Until we see these numbers, Simon Coveney’s department can be reasonably accused of spreading fake news. The housing numbers provided by Coveney’s department just don’t pass a simple smell test — multiple measures suggest the actual housing figure is a good bit lower than reported.

Here’s why these numbers matter. The census shows there were 170,000 extra people between 2011 and 2016, and the average occupancy rate rose over this period, meaning we have more people in fewer places to live.

This is not sustainable.

If we aren’t building more houses, these people will suffer. We won’t be able to solve our homelessness problem, and we won’t be able to help those who want to have a home in the future from taking out ever-larger piles of debt.

The solution to the fundamental public policy problem represented by housing is two-fold.

First, recognise reality and start counting houses accurately. In an address made to the Workers Union of Ireland Seminar in 1967, the late TK Whitaker wrote: “The challenge to us all is to perfect both our methods of appraising what needs to be done and our democratic procedures for achieving our national aims.” That is one of the best expressions of the challenge, and the hope, of public policy for national betterment I have ever come across. Dr Whitaker would take issue with our appraisal method when it comes to housing. We need to fix that if we are to know what needs to be done. Reality must take precedence over all other considerations, or we won’t get the outcome we want.

Second, start building local authority housing again, and at a massive scale. Last year we built slightly over 200, the year before, 64. This would solve the affordability problem and depress house prices around the capital. We must recognise the distributional consequence of this: people who own their homes would lose, on paper, but people who want to own their own homes would win, in reality.

The private sector is not the solution to the housing problem. It is part of the problem, because the housing market does not obey the laws of supply and demand.