Tax policy is all about detail, detail, detail. Who gets hit for how much and in what circumstances. What thresholds apply at what rate, what type of claim is valid and what invalid, and where certain charges apply, and don’t. The US tax code is 5,100 pages long, without including the regulations the IRS actually works under.

Last week two former Goldman Sachs bankers, Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin and National Economic Council Director Gary Cohn took to the stage in the White House to announce the outline of President Donald Trump’s tax plan. And what an outline it was.

Just one page, consisting mostly of bullet points, white space and magical thinking. It was, frankly, embarrassing. I was mortified for them. Really. There were actually fewer details than the Trump campaign plan had.

The Republican Party has had many years to work on this. The administration has had seven months. The last big tax reform was from 1984 to 1986 under President Reagan. Later President Clinton altered the tax code in 1993. President Obama increased taxes on the very wealthy to pay for the Affordable Care Act. President Trump made tax reform a large part of his election platform. And after nearly 100 days in office the head honchos came with a few bullet points.

Magical thinking creates causal relationships between actions and events where none exist. Trump’s magical thinking is that in decreasing taxes massively, the economy will grow, and then the size of the unbound economy, taxed at a lower rate, will be enough to recoup any losses.

Put another way, the idea is that high marginal tax rates severely reduce the incentives for people to work and so by cutting tax rates you are stimulating people to work harder and earn more income, thus raising revenue. This is magical thinking and it has never worked. Like, ever. This is also one of the very few things economists can claim to ‘know’ with some certainty.

Economists should be humble people. We got almost everything wrong in the run-up to the crisis, and even the good advice we gave during the crisis was largely ignored. The current moment is a time of rebuilding in economics generally.

There are, however, a few things economists do know.

We know trade between nations makes most people better off, most of the time.

We know people should specialise in what they do best, and most of the time they should buy in the specialised expertise of others via a market mechanism when they need it.

We know the government is an agent of stability and the redistributive engine of a civilised society.

We know any money spent on early childhood education pays for itself ten times over.

We know that massively cutting taxes and expecting growth to plug the gap just doesn’t work. It is a conservative dream, a fantasy on a par with the belief that the poor are lazy and the ‘tough love’ required is to simply cut their benefits, after which they’ll all go out and get jobs.

Evidence falsifies these claims, especially in the labour market. An extensive literature in labour economics has shown that there is very little impact of taxes on the amount of labour supplied for most people, particularly for prime age working men.

In fairness, the Republican Party has never been big on evidence.

Enriching the already rich

The key points of the plan for Ireland are in the corporate sphere. First, what wasn’t in the outline was as significant as what was: there was no indication of the ‘border adjustment tax’ we discussed in this column a few weeks ago, presumably because very strong lobbying by companies such as Walmart, America’s largest importer of goods and services, made the policy a non-starter in a Congress controlled by corporate interests.

The federal rate of corporation tax will be lowered from 35 per cent to 15 per cent, and there will be a one-off amnesty on US corporate funds held abroad, in places like Ireland. The US has an estimated $2.6 trillion in (yes, trillion, twelve zeroes) overseas retained earnings. A one-off (say) 10 per cent tax could raise $260 billion in tax, or roughly one year’s corporate tax revenue in the US.

Yet more magical thinking in the form of ‘patriotism’ was invoked to show how this money would be fuelled into productive, job-creating economic capital like factories and roads, and not simply end up as dividends for rich people and pension funds. This, by the way, was precisely what happened the last time there was a massive tax amnesty in the 2000s under George W Bush. The Bush amnesty saw sharp increases in share buybacks, dividend pay outs, and mergers and acquisitions. Job creation did not feature strongly, but wealth creation for the already wealthy did, big league.

The two amigos last week gave no indication of how they’d stop this vast increase in the wealth of the top 10 per cent of households, while systematically defunding programs that help the bottom 90 per cent.

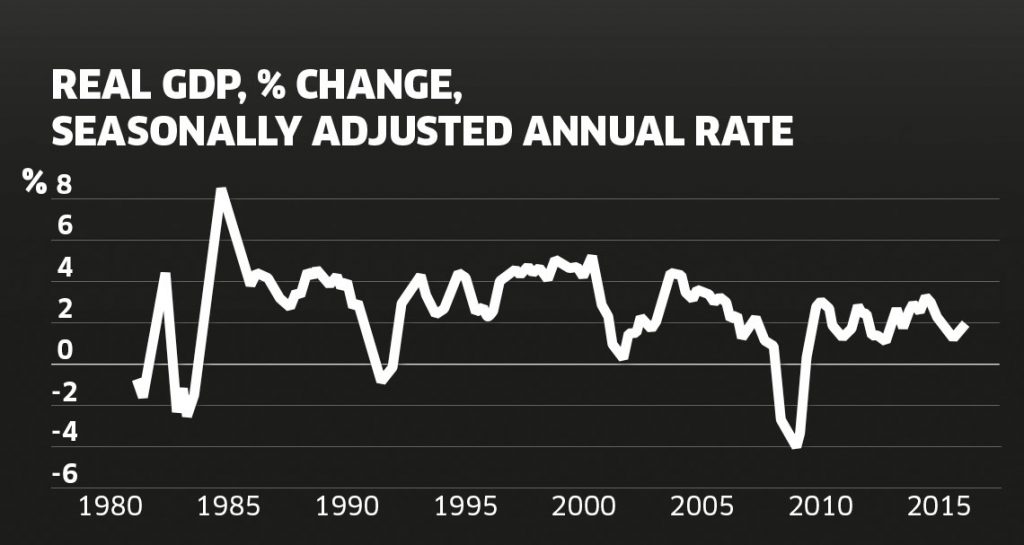

The US economy needs to grow by nearly 4 per cent per year for a decade to make Trump’s numbers work. Look at the figure, which shows the US growth record. It hasn’t grown by 4 per cent since 2002.

The press corps, seemingly inured to this kind of nonsense from the Trump administration, didn’t burst out laughing. They treated the display of one page of bullet points fairly seriously.

The two men spoke for about 15 minutes. At question time, it was amazing how little detail the two most senior economic policymakers in America had on the policies they were announcing. They were asked questions like: in the new three rate personal tax structure, reduced from seven rates, what income bands would apply? They said they didn’t know, it was being worked out.

They were asked about rich people simply moving their money into company structures to save tax, thus causing a massive budget deficit to balloon? They didn’t know. When asked why they were repealing an estate tax which only hits millionaires and the children of millionaires, they flubbed the answer, and said they didn’t have the equation to hand.Here’s an equation. No detail = no plan.

Every country spends its taxes on government expenditure programmes like health, education, defence, and social security. When the amount being spent is greater than the amount the government gets in taxes, the government has to either print money or borrow from the rest of the world. The United States does both, and it has a truly gigantic budget deficit.

Politics over economics

The United States is not Ireland, so its budget deficits do not, in practice, matter. It can create money out of thin air, holds the world’s reserve currency, and so it has the ability to sustain budget deficits more or less forever.

The economics of the budget deficit are not important. The politics are. The Republican party has styled itself as anti-deficit for many years, though in practice the deficit has increased under Republicans and decreased under Democrats. The US has a ‘debt ceiling’ which it continually raises, and this debt ceiling is an instrument of incredible leverage by the Congress over the president.

Under Obama it was actually used to shut down the US government for a short space of time, meaning people didn’t get paid and services didn’t get delivered. President Trump’s plan will explode the deficit. The US Congressional Budget Office projects that the federal debt will grow by $10 trillion over the next decade, and it is at $4 trillion now. There is an old idea in economics. A financial balance is the difference between what you spend and what you take in.

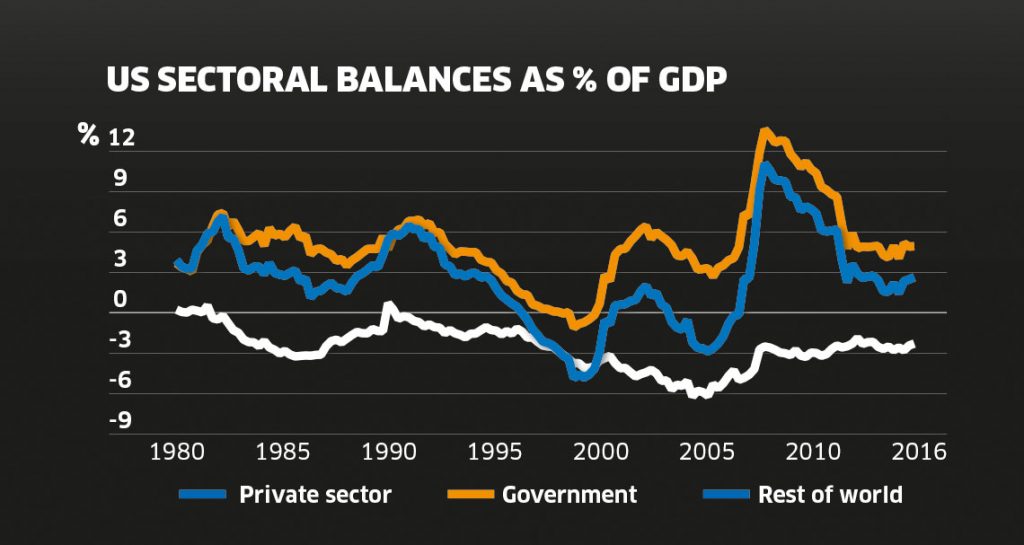

So for the government the balance is government expenditure minus taxes. For the private sector, firms and households, the balance is the amount invested minus the amount saved. The rest of the world’s financial balance is the difference between exports and imports. The idea is that the sum of the private sector’s financial balance, the government’s financial balance, and the rest of the world’s financial balance have to equal zero.

So imagine there are no exports and imports and the economy is like North Korea, and both the private sector and the government are in perfect balance. If the government decides to borrow massively, its balance has to be negative, but because it will have to borrow from the private sector for investment, the private sector balance will have to swing up positively in response. The sum of all three balances will still equal zero.

The sectoral balances graph at left shows those of the United States from 1980 to today expressed as a fraction of economic output. When the government’s balance is above zero, the amount of government spending is greater than the amount it gets in tax, so it’s a deficit.

You can see the vast increase in the deficit from 2000 to 2007 as a result of the various wars the US was involved in. You can see the decrease in the deficit brought about by Obama. You can also see the large increase in investment in the private sector in 2008 as Obama bailed out the banks and the auto industry, and the subsequent decrease in investment to its current low level. The rest of the world has been tipping along throughout the entire period, simply because the US is so large it imports only about 15 per cent of what it needs.

The forgotten stay forgotten

Now let’s think about the Trump ‘plan’ in terms of the sectoral balances. It will massively increase the difference between government spending and tax revenue. The government balance will shoot up again, this time higher than the 2008 spike. The private sector will benefit massively, shooting up as well, but it won’t be the average household who benefits. It will be multinationals, large firms and the rich. The forgotten men and women stay forgotten.

The importance of the Trump ‘plan’ in terms of Ireland is simple: it will create a vast sucking noise as the funds which enrich the IFSC and other business-friendly financial services destinations head back to the US. If the tax code is changed to remove loopholes where US firms can hold retained earnings offshore, we might see a dent in our US foreign direct investment.

Luckily, we have Brexit (never thought I’d hear myself say that), and this means Ireland remains a key access point for the European Union, which we know is a key driver of FDI here.

Our corporate tax rate will still be lower than the 15 per cent charged in the US, and probably lower still if you consider effective tax rates. Trump’s tax ‘plan’ may well be a threat, but only if it turns into an actual plan. We have to await the detail to understand its likely impact. When it comes to tax, the devil is in the detail, not the dynamic.