Noonanomics

There are two Irelands. The one concerned with the big-picture stuff, the macro-economic story, will celebrate outgoing Minister for Finance Michael Noonan, and it will do it by mentioning official statistics. The other Ireland, the one concerned with micro-economic issues of household debt, inequality, child poverty and homelessness, might damn him.

He took over as Minister for Finance with the freedom of a huge parliamentary majority, but under the constraint of having to implement an austerity programme under way before even the troika arrived.

This is not something our official history seems to have grasped: his predecessor, Brian Lenihan jr, began implementing an austerity programme well before the troika came to town. Very hard decisions had to be made by Noonan and his colleagues, but ultimately there was always the big bad troika to point towards if decisions had to be justified to ordinary Irish people.

The government implemented austerity policies comprehensively, and was rewarded by the troika with a deal on the promissory notes – for which we can thank Noonan’s relationship with former ECB board member Jörg Asmussen – and better terms and conditions on the repayment of our debt. The troika’s fiscal shackles have been replaced by the fiscal rules which constrain Europe’s finance ministries from deficit spending.

It is important to note that Noonan’s formal role is different from his predecessor. Lenihan had control over both taxation and spending policy. His brief was enormous, and the two neglected aspects of this brief – public sector reform and the management of Ireland’s international relationships – are partitioned in the current set-up.

The Minister for Finance has two big jobs: getting taxes into the country’s coffers and dealing with the international financial aspects of funding a small open economy.

The Minister for Public Expenditure and Reform, currently Paschal Donohoe, spends what the Minister for Finance gives him and tries to keep the reform agenda going within the public sector.

Noonan delivered seven budgets in six years. One was a handbrake-style supplementary budget, but each of them changed the nature of Ireland’s taxation system incrementally.

When Noonan took over Finance in early 2011, it was understood that increases in taxation would be coming, and because of the structure of our economy and the nature of who is taxed, these increases would have to be to income tax first and foremost. One way to measure that is in terms of the tax wedge.

The tax wedge is a measure of the tax on labour income, which includes the tax paid by both the employee and the employer. Think about it as the ratio of total taxes divided by total labour costs.

Ireland has a very low tax wedge relative to the rest of Europe because employers contribute much less to the pot than in other countries. In Ireland in 2011, the tax wedge for a single worker was 25.8 per cent. Today, it is 27.1 per cent.

Bread and butter

Noonan removed hundreds of thousands of people from universal social charge taxes, the finest and most progressive income tax Ireland has ever seen, and a truly hated one as a result of its completeness.

He introduced Vat exemptions on tourism and hospitality, which increased employment in this area, but which have probably run their course as a policy. He did deals with sectors in exchange for their help in managing the economy.

I recall attending one meeting which Noonan addressed, where he was questioned on the pension levy he introduced to fund changes to other parts of the taxation system. The speaker, a passionate advocate of private pensions, railed at Noonan for plundering the pension pots of the private sector. (The levy was originally applied at a rate of 0.6 per cent every year on the value of pension assets.)

Noonan stood, impassive, as the man wound down, and then deftly cut the legs out from under him. “Spoken like a man who only has half the story. Go back and ask your friends in the pension sector for the other half.” The man sat down and looked like he needed a hug.

In Europe, Noonan won the approval of just about everybody for his handling of the Irish economy.

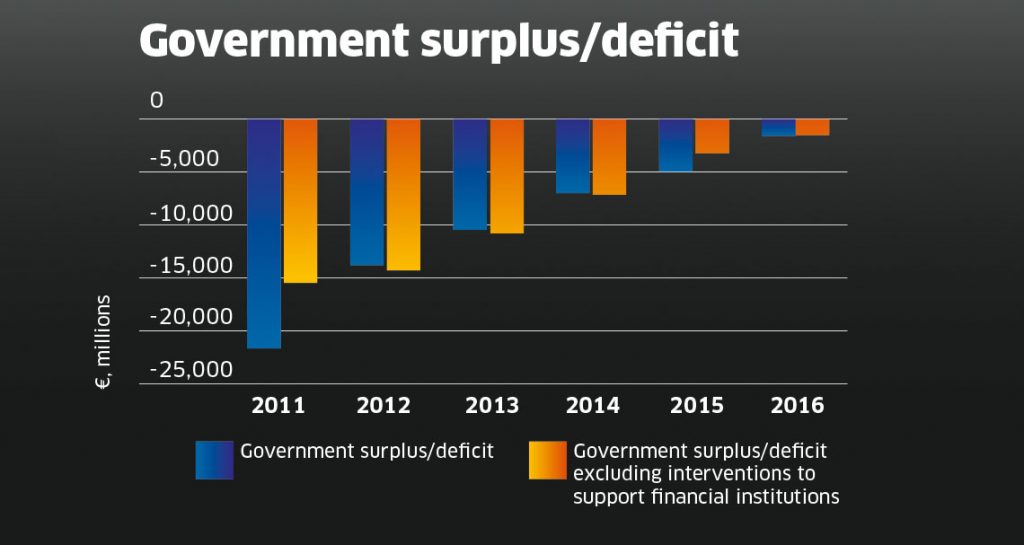

The figure shows the government deficit shrinking over Noonan’s time, and it shows the deficit with and without bailing out the banks.

I spoke with one French economist working at the European Commission who attended meetings with Noonan who said of him: “Monsieur Noonan, he does not fuck around.”

This is true. Despite not being in the best of health, Noonan has continued to try to keep Ireland as open for business as possible, given the current circumstances. He recognised the need for Ireland to be at the front of changes to the global taxation system and a key partner in the OECD’s Base Erosion Profit Sharing scheme.

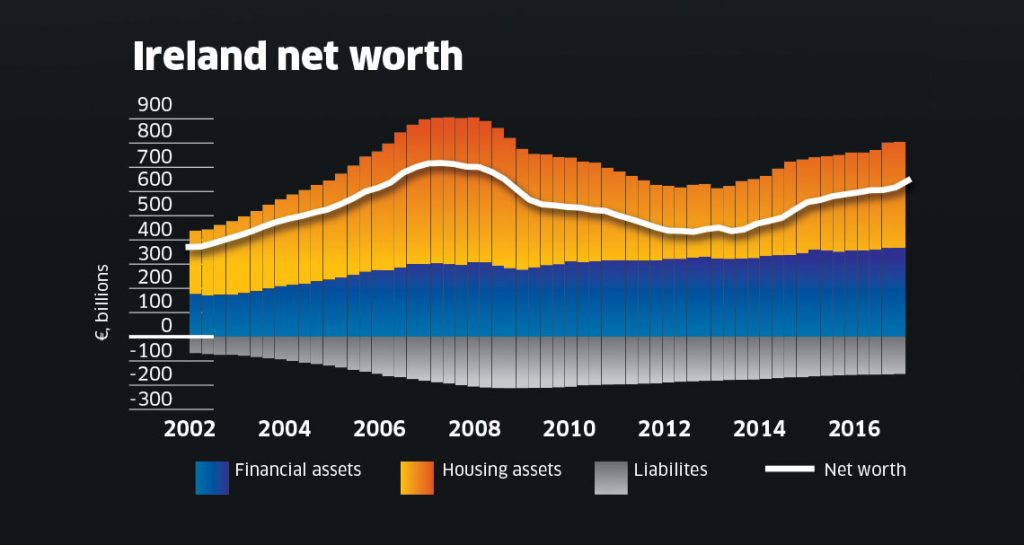

The figures show the rebound of the economy in terms of its assets and liabilities – household net worth has jumped markedly since 2012, and employment has increased markedly, even though credit extended to households is back at 2005 levels.

In terms of macroeconomics, and the bigger picture, Noonan can be declared a winner, especially for those people who own houses and financial assets. Household net worth is calculated as the sum of household housing and financial assets minus their liabilities. Ireland’s net worth is around €663 billion. When Noonan took over, it was €469 billion.

So what is Noonanomics? It is a cautious combination of carefully judged sectoral policies – Vat breaks for tourism, Knowledge Boxes for research and development – combined with handshake deals with the key players in these sectors.

Noonan’s voice, and his stature as Minister for Finance, helps makes these policies possible. It does not hurt, when doing these deals, that Noonan sounds like he might murder you for sport as he stares at you like a maths teacher from the 1950s.

Noonan was dropped into the Programme for Government negotiations when they had stalled. Reports are that he basically stared at the Independent Alliance, told them he’d have plenty of money for their pet projects, and that was that. Deal done.

Remember, Noonan is constrained by the fiscal rules and by the amount of money he has to try to tax. He also can only change the taxation system incrementally. And he can’t change the corporate tax system. Given these constraints, sectoral policy-making is the bread and butter of his policy-making.

Children of austerity

Noonan’s role as Fine Gael talisman is a million miles from his disastrous turn as leader of Fine Gael in the early 2000s, and his term as Minister for Health which, but for the global economic crisis, would be his legacy.

Had he retired as Minister for Finance before the 2016 election, he would have been beatified. But his handling of the fiscal space debate, his role in changing Nama’s terms of reference to speed up asset disbursal, his courting of vulture funds to bring funding into Ireland, his recent treatment of the Public Accounts Committee over Nama, his series of regressive budgets and his insistence on winnowing the tax base by removing the USC all stain that macroeconomic copybook.

I said at the outset of this piece that there were two Irelands, the one from the macroeconomic view, and the one from the microeconomic. If Noonan’s legacy is an economy with better fundamentals and a near-zero primary budget deficit, it is also of an economy that has not recovered equally.

A new book entitled Children of Austerity, published by Unicef, pulls out the salient points. In 2008, 18 per cent of all our children lived in relative poverty. By the end of the austerity period, that number had shot up to 29 per cent, and the composition of those children who were in poverty had changed too, with the proportion of children living in jobless households rising very sharply over the crisis.

In 2008, only 15 per cent of all households with children reported living in conditions of material deprivation. By the end of the crisis, that was closer to 30 per cent.

The key immiserating measures? Budget 2011: cuts in welfare for working age of 4 per cent, child benefit cut by 10 per cent. Budget 2012: increases in income taxes, introduction of household charges, cuts in fuel allowances, cuts in pensions and restrictions of tax reliefs, reduction of back to school payments, cut in child benefits for families with over three children. Budget 2013 began a clawback of some of these measures, but they all have yet to be restored. Ireland’s relatively generous welfare system stopped the crisis being even harder on families, but some of these measures – like reducing medical cards – could have been avoided.

Ireland’s tax base is too narrow. We rely on income tax, Vat and customs and excise duties to make up the bulk of the money the state uses to fund its services. The introduction of a property tax was successful. The introduction of a water tax was not, to put it mildly. Thousands of litres of ink have been spent on analysing that particular failure, but Noonan’s lack of influence in stopping such a bad policy getting off a discussion paper and into policy was notable.

Yes, there are two Irelands. At the national and international level, despite the failings of Nama and the presence of vulture funds within Ireland’s economy, Noonan leaves office with his job done and his head held high. At the microeconomic level, however, the children of austerity will not thank him.