Like a train coming toward us through thick fog, the shape of Britain’s exit from the European Union is becoming clearer. The impact is, as yet, uncertain. Whatever happens, the chances are it isn’t going to be good. The worst of all worlds for Ireland is a situation where Britain imposes a hard Brexit.

A hard Brexit means tariffs and levies on the goods and services our businesses sell. The heart of the European Union is its customs union – the definition of a customs union is a common external tariff we have to share as part of the EU.

A hard Brexit means potential quotas on the movement of our workers, and even caps on the movement of our capital. A hard Brexit means throwing our relationship with Northern Ireland into sharp relief.

Where exactly do we draw the line between North and South?

Where do we go together, after Brexit? The right arrangement now looks like some sort of free trade agreement between the EU and Britain. Britain has to want that and be prepared to compromise to get it, and spend years in negotiations, to boot. A free trade agreement may still come with borders.

As UCD historian Diarmaid Ferriter wrote in 2005, the economies of Ireland, both North and South, are interlinked and interdependent, but they are not aligned. Since the 1920 Government of Ireland Act gave effect to partition, the Republic and the North have evolved in very different directions, and in 2017 they are distant relatives, rather than kin.

The practical implications of this separate evolution can be seen in our coverage of the upcoming elections in the North. So far, the election campaign hasn’t made it onto the Six One News much, nor has it captured the imagination of our minority government which is focused entirely on the fallout from Brexit.

As we’ll see, the two parts of the island are united in their vulnerability to external shocks, Paradoxically, their dependency upon the whims of others may well shunt the two administrations together.

How did we get here?

The power-sharing arrangements instantiated by the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 have ground to a halt yet again, this time over a fairly spectacular policy cock-up.

The renewable heat incentive scheme provided a subsidy when applicants switched from burning fossil fuels to wood biomass heating, This RHI subsidy was designed as a flat rate — providing no incentive to be efficient. The scheme was also designed without a cap on the amount of the subsidy an applicant could receive, meaning the more heating you do, the more money you’ll make. For every £1 you spend, the scheme returns £1.60 to you. Farmers are now heating empty sheds, and it is projected to cost Britain nearly half a billion euro over the next 20 years. Now that’s a cock-up. Economy minister Simon Hamilton has come up with a scheme – ostensibly approved by finance minister Máirtín Ó Muilleoir’s wonks – that looks like a credible two-stage fix. Nonetheless, the whole thing has caused another election ten months after the last one.

British prime minister Theresa May has now sketched her plans for a hard Brexit. Her opposing EU negotiators may or may not respect the border question between North and South during the negotiations triggered by Article 50. The Northern Assembly has just under six weeks to election day, after which the two large parties which couldn’t work together before the election will surely be returned to power in roughly the same configuration.

Donald Trump has taken over the White House pledging protectionism, but honestly, given how many lies he told to get the office of president, who knows what he’s going to do once he’s there? The markets are happy, but everyone else is terrified.

On both parts of the island, Ireland’s policy makers are caught between powerful forces. We in the South will negotiate as part of the EU, which has set its face against allowing the British concessions on free movement, and yet the best option for us is the one that maintains an open border between the Republic and the North. Those in the North will negotiate as part of Britain, despite 55 per cent of voters deciding to remain within the EU. In both cases, our shared interests are not paramount in the minds of the groups we’re a part of.

Brexit, Trump, and wood biomass heating. Not quite the combination we would have expected this time last year.

Brexit and the economies of North and South

Analysing the Brexit result in the North is fascinating. The vote breakdown embodies the complexities of understanding the North.

The North voted to remain within the EU. More than 55 per cent of it wanted to Remain, but largely unionist or rural areas voted Leave, in places like South Antrim, Upper Bann, East Belfast and Strangford, while largely nationalist areas like West Belfast had a lower than expected turnout, and some unionist areas like North Down voted strongly for Remain. We will need a deeper analysis to understand why rural communities in South and East Antrim voted for the removal of EU subsidies which would cripple them financially. Not even every DUP MLA voted Leave. The Brexit vote reveals subtlety and nuance in the North that we in the South know little about.

Every economy can be understood in terms of its people, the structure of what it produces, what its households and industries consume, what its central and local governments spend money on, what gets invested in, and who they trade with.

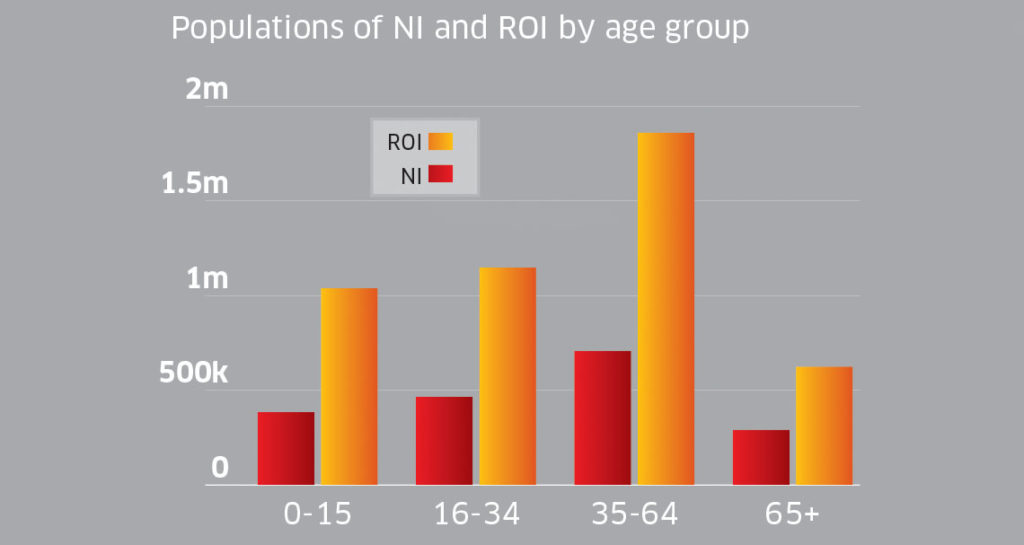

Economically, the North is a very different economy to the South’s. There are 1.8 million people living in the North and 4.7 million people living in the Republic. Economic output per person in the North in 2014, the last year for which good data is available, was about €21,800. Economic output per person in Ireland in the same period was around €41,000, but remember our figures are inflated somewhat by the presence of multinationals.

It is very difficult to compare the two economies directly, because the Republic is necessarily designed as a fully functioning state, while the North still outsources many of its state-like functions to Britain, and is set up as a regional economy which absorbs net transfers from the rest of Britain at between €9.2 billion and €11.5 billion per year.

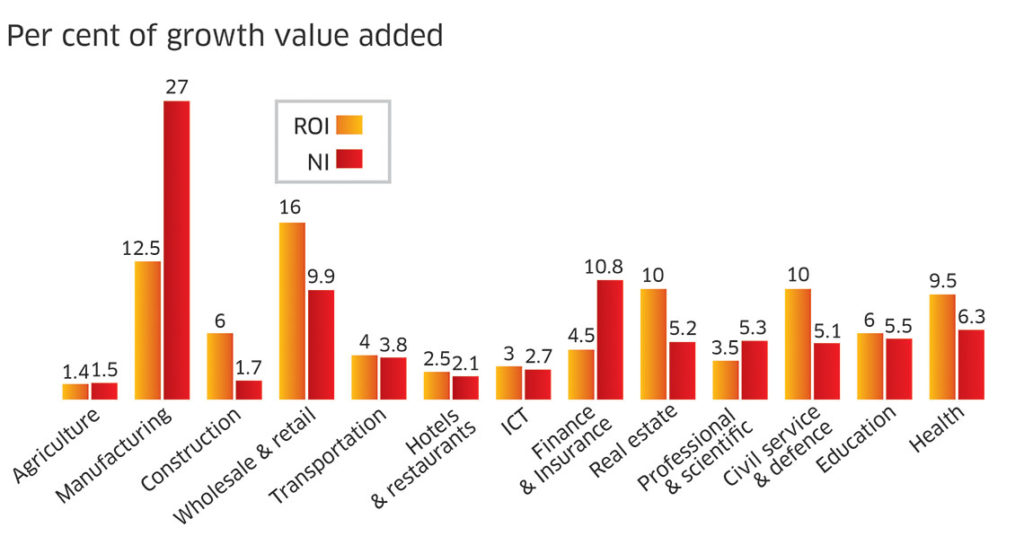

A fairly clean measure we can use to understand the two economies is called gross value added, which is equivalent to GDP with subsidies added in and less indirect taxes. When you break out gross value added by industry for the two economies in 2014, a really interesting picture emerges.

Structurally, we are very different economies in terms of what we produce. The North derives much of its gross value added — around 27 per cent – from manufacturing, with another 11 per cent coming from finance and insurance and 10 per cent from wholesale and retail. It also produces more on health — around 9 per cent – relative to Ireland’s 6 per cent.

Overall, the picture is of an unbalanced economy. If manufacturing succumbs to the rise of the robots and many of the jobs associated with manufacturing disappear, the North is in serious trouble.

The Republic has a more balanced industrial output, which you would expect given its relatively larger size, but still attributes 16 per cent of its output to wholesale and retail and 10 per cent in real estate. It is much more focused on the professional and scientific sectors which generally produce proportionately more output. Structurally, the two economies are quite dissimilar. In any reunification scenario, many of the differences would be eliminated, which might generate efficiencies and productivity increases in some sectors — Irish manufacturing, say — but others would be wiped out.

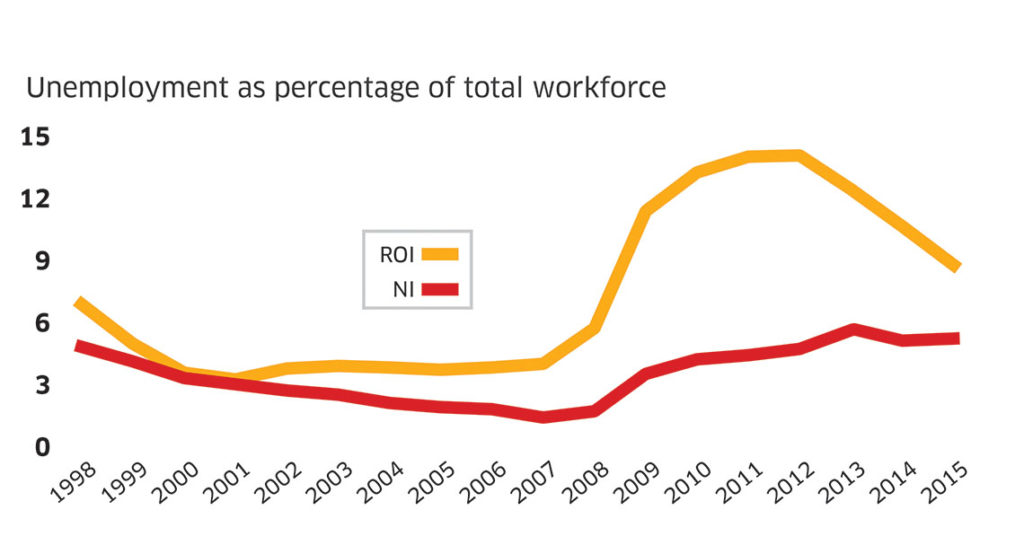

The Republic had an economic crisis of existential proportions; the North did not. The unemployment figures tell the story very well, but household debt figures are also comparable. Employment levels in the private sector in the North are well below other British regions on a per head of population basis, and even further below the South. The North has a significantly lower labour force participation rate than the Republic, and those workers it does have are far less productive. Household debt levels are much higher in the Republic than in the North, for obvious reasons.

Thinking of each economy as a separate state, we can think about what these two states spend their taxpayers’ money on. The North absorbs substantial cash from the British treasury of around €22 billion per year in gross terms, which it then partly repays with about €11 billion in taxes. The deficit is substantial and has a warping effect on the economy, as we will see. In many respects, the North is a welfare state with a private sector bolted onto the side.

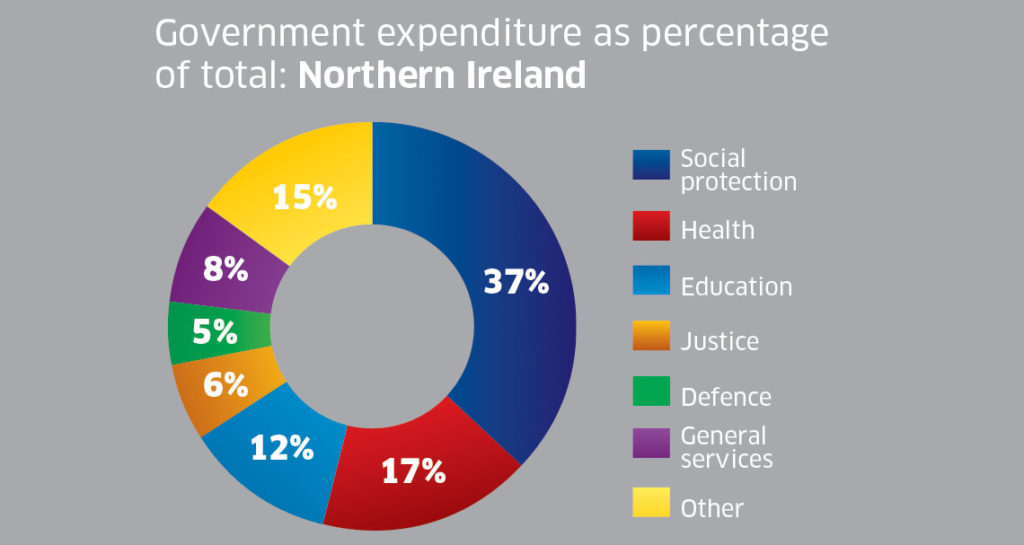

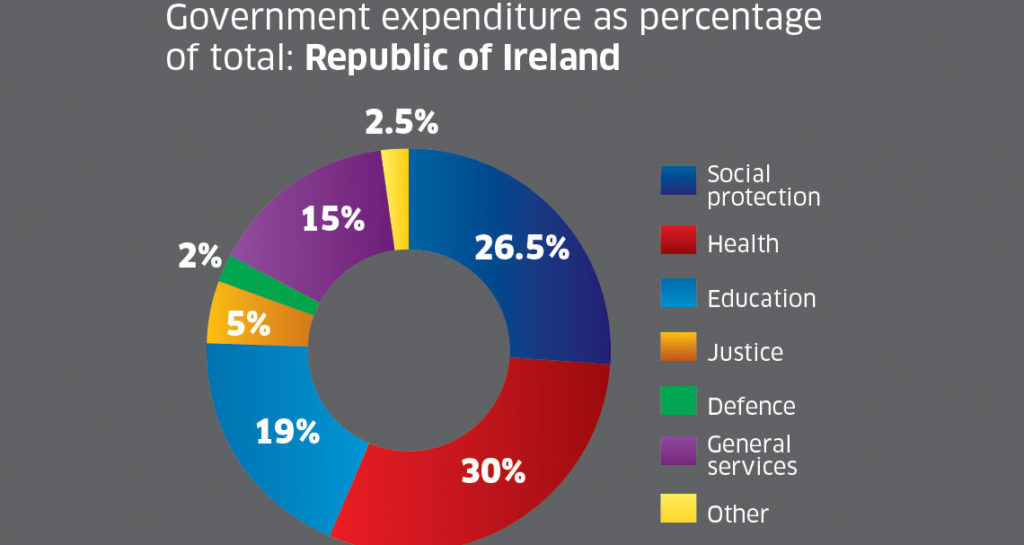

These donut graphs compare the two states in terms of the percentage they spend on things. The Irish government spent around €46 billion in 2014, and 27 per cent of that was social protection expenditure. The same figure in the North – which, remember, did not have an economic crisis like we had – is 37 per cent. Some 30 per cent of what they spend in the North goes on health; in Ireland that figure is 17 per cent. Interestingly, the North spends less on education (12 per cent) than the Republic (17 per cent).

The overall picture of the North is an economy heavily dependent on the public sector and a few key industries like manufacturing, with little else going on.

Without substantial transfers from Britain, living standards in the North would be far, far lower than they are today.

Unification?

Brexit’s result has also begun a conversation about reunification between the North and South, probably the first such conversation for 80 or 90 years. There is no prospect of a reunification unless a majority on both sides of the border wish it, but I think it is no harm thinking about what a reunification would look like.

The most substantial study on the economic effects of reunification was done by academics Kurt Hubner and Renger Van Nieuwkoop in a consulting report. They claim Irish unification could potentially lead to a €36.5 billion GDP increase for the united Irish economy over an eight year period between 2018 and 2026.

Growth in the North would increase rapidly, perhaps growing between 4 per cent to 7.5 per cent. Growth in the South would slow to 0.7 per cent to 1.2 per cent as it struggles to afford this new regional economy.

Hubner and Van Nieuwkoop looked at a few scenarios, but thought the gains would come through five main channels. It should be said their modelling work was done before Brexit happened. I am not a fan of this work, for various technical reasons, but it is the best work out there at the moment and they are right to look at five main channels reunification would affect.

Where will the growth come from? First, growth will come from a combination of the tax systems, with the North adopting the rates and regulations of the Republic. The report claims that this adoption would lead to an increase in foreign direct investment in the North and lead to economic growth.

Second, growth will come from breaking down trade barriers and integrating sectors. This would apparently allow firms in Northern Ireland access to the common market. The modelling in the report assumes unification would lead to lower trade costs in terms of currency and transport between Ireland and eurozone countries, and that the reduction in trade costs would lead to an increase in per-capita income. In any Brexit scenario, this would amount to keeping the current trading conditions and EU subsidies the North enjoys.

Third, growth will come from the use of a common currency. The report suggests the introduction of the euro would lead to a boost in the North’s exports in the short term.

Fourth, growth will come from improvements in productivity. The model suggests that a convergence of productivity levels between the North and South would have a positive output on both sides of the spectrum, but doesn’t suggest the mechanism for this productivity increase.

Fifth, growth will come from fiscal transfers. The North’s €11 billion fiscal deficit would be financed by the Republic instead of Britain. The model suggests that this will lead to a reduction in public spending due to the fact that there would be no need for two separate political structures on the island.

Hubner and Van Nieuwkoop’s model has a lot of flaws, but it remains the starting point for any discussion about reunification, until something better comes along.

I think it says a lot that the best work we have on the economics of reunification is a single consulting report based on a single, flawed model. More research is definitely required in this area. Credible agencies like the ESRI should look into analysing the impact of reunification on both economies in a careful way.

Doing a back-of-the-envelope calculation, if both sides were to decide on reunification, it would require two big changes at the macro level. First, ‘we’ would need substantial sums from the EU to reunify. The reason? The capital stock in the Republic is rubbish compared to the North’s.

Over the last five years, the North has averaged 10 per cent of its total expenditure on capital like roads and hospitals. The Republic has never in 40 years managed 6 per cent. The practical implications of this are obvious. Which health system would Mrs Murphy from the Falls Road want? The NHS, or the HSE?

Second, income taxes have to increase in the South to afford the North. We wouldn’t be on the hook for the full €10 billion right away, of course, but we would eventually have to foot the bill for this new region.

We’d gain more workers and more in tax revenue, but running the North’s economy would not be cheap. Irish income taxes would have to rise by 2 per cent or 3 per cent, for example, to raise the €10 billion. Irish citizens would also be able to access the excellent healthcare and educational services in the North, and so costs would rise there too. I am not sure there is public support for increased taxes to pay for reunification.

The economies of the North and the Republic are different, and it would take a generation to merge them even partly.