Here’s where we are at the end of the first month of 2017. Theresa May is in London, trying to take Britain out of the European Union. Donald Trump is in Washington DC, trying to build walls and erect tariffs. Angela Merkel is in Berlin, veering to the right to stay in power. In France, Marine Le Pen, a hard-right candidate, is likely to clash with two other right-wing candidates to see who can be president of France.

At the annual mutual love-in of Davos, the Chinese premier promised to lead the world in terms of openness. This is code for: lead the world by stepping into the space left behind by a retreating US. Global power is pivoting to Asia. South American economies are sliding into their familiar commodity-based cycles of debt-induced recession, while the Middle East tears itself apart in two wars — the one in Syria, and the one in Yemen. You’re not even safe in the Arctic, because that is melting at an unprecedented rate, paying no heed to what the climate denier in the White House says.

(I am available for children’s parties, by the way.)

I have argued in this column many times that Ireland needs to think carefully about its place in the world and its model for economic development. We are not big enough to influence events. Ireland only represents 0.21 per cent of world output. It is not Frankfurt’s way or Labour’s way, it’s just Frankfurt’s way. We are sovereign only to the extent we are allowed to be sovereign by other, more powerful forces.

Ireland’s 100-year-old democracy has survived two World Wars. It should be able to survive what might be the end of the second great period of globalisation, from 1973 to 2017. But while we might survive, how do we thrive?

The historian Joe Lee once wrote that “small states must rely heavily on their strategic thinking to counter their vulnerability to international influences”. Where is the evidence of strategic thinking in the age of Trump? It feels like we’re still working to the strategy of the 1950s.

Since the 1950s, Ireland has prospered by seeking investment from abroad. It is our one big idea. Every policy initiative is bent towards securing investment from abroad, and we have become very good at it. Export-led growth is our mantra, obsessively practiced, and our fall-back position when things get tough. Imposing austerity? Offset it using multinational jobs. Brexit? Secure more jobs in the City of London. Trump? Sure, everyone loves us over there, and even if Trump does cut corporation taxes to 15 per cent, we still charge them less. We’ll be grand.

Think about how often you see job announcements from multinationals on the news. Think about how large parts of Dublin, Cork and Galway are given over to the European headquarters of Huge Company X or Y. Think about all the government departments and hundreds of quangos the government has. You might not have heard of half of them. But you know what the IDA does. Read the IDA’s strategy from 2015 to 2019. They want 900 new investments for Ireland to create 80,000 new jobs.

I’m not bashing multinationals or the IDA but they aren’t here for the craic and the songs. They are here for market access to the European Union and extremely business-friendly rules, regulations and taxation. This approach has some costs, and some benefits.

The benefits are obvious: high-paying jobs and tax revenue. There are over 174,000 people employed in foreign-owned enterprises in Ireland, representing almost one in ten workers in the economy. Each year, these companies pay billions in wages to Irish employees, spend billions on fixed capital investment in Ireland and contribute billions in corporation tax to the exchequer. The costs are less obvious. Multinationals deform our economy, they make it hard to measure, they damage the reputation of the economy by their tax-avoidance practices, they add enormous risk to our tiny nation’s balance sheets. Sometimes, they just use us.

There’s an industry called ‘non-bank financial intermediation’. You might know it as shadow banking. Shadow banking is any financial activity that takes place in an unregulated way. Because these entities aren’t banks, they can do things banks can’t do. Ireland is a major hub for shadow banking. The Irish Central Bank estimates €3.8 trillion worth of shadow banking activity passes through, or is held in, Ireland. That’s 15 or 20 times the size of the entire Irish economy. We facilitate the movement of hot money around the planet. Some financial services are socially beneficial. Most are not. They help the rich get richer. By encouraging, endorsing and sometimes underwriting this behaviour, Ireland becomes complicit in it.

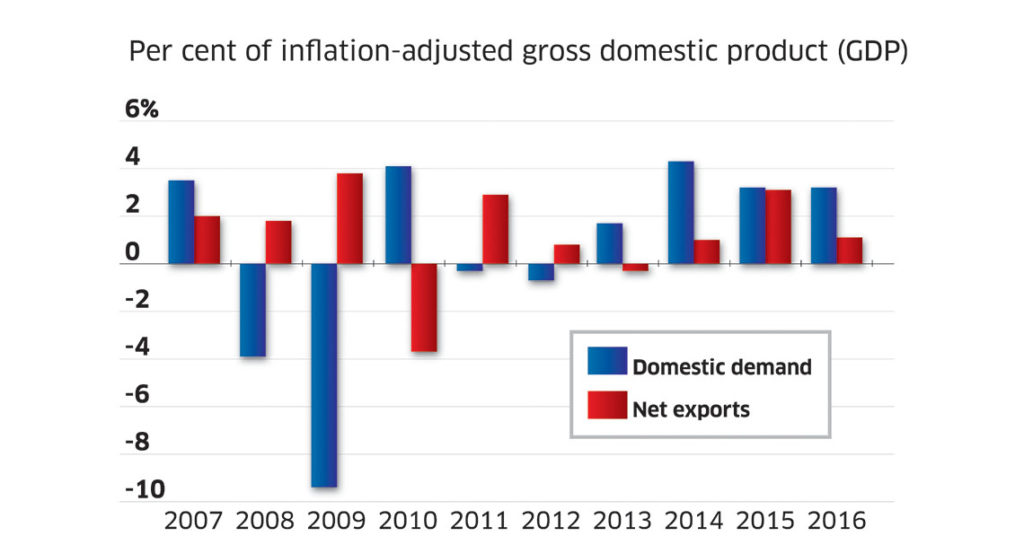

We even tend to overstate the benefits I described above. Much of the growth we have seen since austerity ended in 2013 has not come from multinationals. It has come from us, from domestic Ireland (see figure 1 above). In 2014, for example, 4.3 per cent of our growth came from the domestic economy. Only 1 per cent came from net exports. Faced with these facts, why are we so enamoured with the multinational sector? Nine out of every ten jobs are created either by the domestic private sector or the public sector. It dwarfs the multinational sector everywhere, except policy-making circles and the media.

Labour’s share

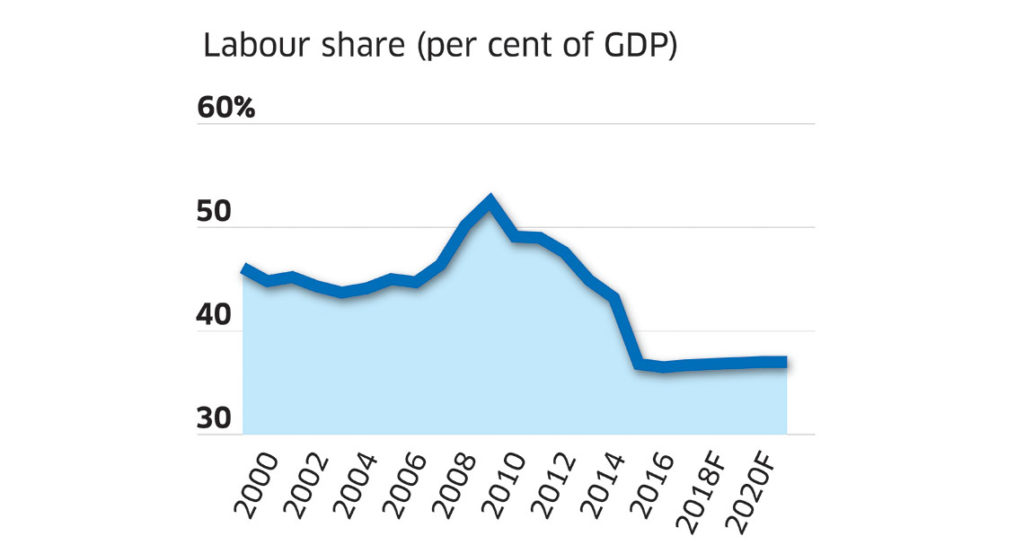

A historical perspective never hurts. James Connolly once wrote that the cause of labour is the cause of Ireland, the cause of Ireland is the cause of labour. How is the cause of Ireland helped by funnelling trillions of barely regulated dollars around the globe? Just compute labour’s share of our gross national product to see. No surprises that it’s falling (see figure 2 above).

In 1999, workers took home 46 per cent of the value of the stuff we produced as a nation. In 2017, workers will take home 37 per cent. You don’t have to be a socialist like Connolly (and I’m not) to see there’s a problem here. Labour’s share is forecast to remain flat for another five years.

In an unequal society, this falling share creates a kind of paradox of relative expectations. The best example of this is decking.

During the boom from 2002 to 2007, despite our climate, society thought it best to put a debt-financed deck in the back garden. The deck was then to be admired as we all went to barbecues at each other’s houses. Some 30 seconds after the first barbecue ended because of inclement weather, the deck became slimy with algae and has existed as a trip hazard ever since.

Now, as then, neighbours use large purchases to compete for relative status. Come and look at my loft extension, or my kitchen extension. We’re all supposed to want decks again, but with lower incomes and less of a slice of the pie. That creates a tension society must manage.

Tariff on goods

The question becomes one of what economic model works for Ireland after 2017.

Boston or Berlin? More like Sunderland or Shanghai.

In 2006, the economist Michael O’Sullivan wrote a brilliant book called Ireland and the Global Question.

The global question is: when economies are increasingly interdependent, how do you manage your economy, society and public life?

When Donald Trump can put a tariff on your goods and services, when Theresa May can alter the labour market your children face, how do you achieve your goals? The answers to the global question changes by country and over time.

Tánaiste Mary Harney once posed the question as Ireland choosing between Boston and Berlin.

Ireland is a European country in terms of our ancient and medieval history, our geography, our democracy. But culturally and economically, we are much closer to the US. We live in cities built by the Norse or the Normans, but we watch US TV on Netflix. Economic policy is decidedly Boston, not Berlin: low business taxes, low regulation, a focus on the individual as the object of economic development rather than, say, the family or the county or the nation, and of course, foreign direct investment.

Mary Harney couched the differences between Boston and Berlin in terms of belief, not structure. In an address to the American Bar Association in 2000, Harney said: “What really makes Ireland attractive to corporate America is the kind of economy which we have created here. When Americans come here, they find a country that believes in the incentive power of low taxation. They find a country that believes in economic liberalisation. They find a country that believes in essential regulation, but not over-regulation.

“On looking further afield in Europe, they find also that not every European country believes in these things.”

But do we? Do we really believe in these things in 2017? Are we more Sunderland and Shanghai than Boston and Berlin? As power pivots to Asia, and as Britain reaches out for older relationships, will we find ourselves being drawn into the future, or the past?

Last week, the Minister for Finance, Michael Noonan, announced that Ireland has applied for membership of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank to increase our links to Asia and China, and their money. Also across most of the radio stations last week: calls for Ireland to leave the European Union post-Brexit and join the Commonwealth.

Now think about the major public reactions to policy mistakes since the onset of the 2007 crisis. The revolt of the elderly at the removal of free medical care for the over 70s in 2008 and 2009. In February 2009, more than 100,000 people protested at the Irish Congress of Trade Unions. In 2010, 40,000 students marched against increases in their fees. The Ballyhea anti-bank debt protests were small scale but continued for years. At every hospital downsizing, thousands marched. The protests at wind and energy policy changes in 2013. The anti-water-charge protests from 2013 to 2015 mobilised hundreds of thousands. The ‘home sweet home’ initiative was little more than a marketing exercise for ‘awareness’ about the real problem of homelessness, and even it drew thousands to its protests.

These protests expose the tensions Irish people feel at the imposition of policies they don’t agree with. They are identifying problems that the political system either generates or can’t deal with. Expect more protests in the future as the void between what can be changed by policy and what can’t gets wider.

Ireland and the global question in 2017

It’s not all doom and gloom. Ireland has a much more educated workforce than it did in the past. That might sound like marketing speak, but it isn’t. In 2015/2016, 217,530 students were in the higher education system alone. More were enrolled in the further education system and in private education. By contrast, in 1965, only 15,441 people went to third level.

If 1965 is too far back for you, think that in 2004, only 77,491 students went to third level. This huge expansion has put massive pressure on the third-level system, but it also means our graduates are much more adaptable than they were in the past, and much better trained. However things change, they can adapt.

Ireland has a deep deficit in capital spending. Since 1950, we have averaged spending of about 3.2 per cent of our GDP on investment. Even at the boomiest of the boom, we only spent 6 per cent. How and where we choose to allocate our capital in the future, where new roads get built, where new hospitals get built, where new schools get built, will determine the shape of the country for years to come. Simon Coveney’s ‘Ireland in 2040’ strategy will address some of these issues, and it is coming out soon.

Ireland’s workers take home 37 per cent of the produce of the economy. Policy can help change that figure, moving us from Boston towards Berlin, and increasing it so that when we have to answer the global question, we have the resources to do so.