The business cycle is a tricky concept. Economists have studied why economies experience large shifts in demand for good and services for centuries. Many indicators of economic performance (or lack thereof) exist, and as many theories exist to explain them.

You'll also want to read Barro, chapter 8, before this lecture.

Economists pretend we can measure the business cycle, and make serious and deep efforts to understand it as a profession, but economists are largely powerless to do anything about business cycles. We experience them like anyone else. Even the wikipedia article defining it is continually in dispute.

What is a business cycle?

Well, we call it a 'cycle' because there seems to be an up and down relationship between real (or actual) GDP and trend (or potential) GDP. When an economy is below it's trend GDP, it might be heading into a recession. When an economy is above it's trend GDP in terms of it's real GDP, it might be experiencing a boom period.

GDP is assumed to break down into two parts, Real trend and cyclical. The cyclical part of GDP is the real part minus the trend part, and that is what we want to explain in this section of the course.

Barro shows us the proportionate deviation from trend GDP of the US Economy. What does it look like for Ireland?

It looks like the figure below, where our 'output gap' to 2005 is shown.

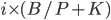

We'd like to explain the existence and movement of business cycles through an equilibrium framework, so we'd like to consider changes in GDP, Y, C, etc, as they are affected following a shock, say, to technology,  , or to investment,

, or to investment,  , or access to credit (as we've seen recently).

, or access to credit (as we've seen recently).

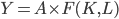

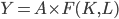

The starting place for an equilibrium business cycle model is the production function,

.

.

In the short run, the capital stock  , is fixed. The assumption is that if

, is fixed. The assumption is that if  changes (say, computers fall out of the sky), that will effect

changes (say, computers fall out of the sky), that will effect  only.

only.

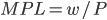

We derived the following two results in a previous lecture: the marginal product of labour will equal the real wage rate in equilibrium  . Similarly, the interest rate will equal the marginal product of capital, which will equal the return on capital minus the depreciation rate:

. Similarly, the interest rate will equal the marginal product of capital, which will equal the return on capital minus the depreciation rate:  .

.

Our equilibrium business cycle model will have to explain changes in consumption, saving, and investment, over the business cycle.

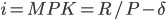

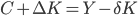

So, we need an expression for a household's budget constraint at any moment. Luckily, we have one:

.

.

This equation tells us the household's consumption  and saving

and saving  decision is dependent on it's real wage rate

decision is dependent on it's real wage rate  and it's real asset income,

and it's real asset income,  .

.

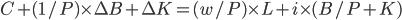

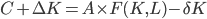

If we aggregate all the household's budget constraints in the economy, we have

,

,

which says that consumption and net investment is equal to real GDP minus depreciation, or real net domestic product.

If we substitute in the production function  , we get

, we get

What will the income effect be on  from a change in

from a change in  ? Because depreciation is fixed in the short run, we have technology increasing real income, and consumption will rise. The intertemporal substitution effect fights against the income effect on this, so no sharp prediction can be made.

? Because depreciation is fixed in the short run, we have technology increasing real income, and consumption will rise. The intertemporal substitution effect fights against the income effect on this, so no sharp prediction can be made.

Consumption and Investment

What does consumption and investment look like over the business cycle in Ireland?

We'll go through more examples in the lectures.

Related articles

- Recession fears as US economy shrinks for first time since 2001

- Beware the dreaded R word

- Economics for Business Lecture 15: Growth Models

- China announces $586-B stimulus plan

- Global stocks shaky amid economic woes